A SIT-DOWN WITH

Cristiano Travaglioli

The Great Beauty, Youth, Il Divo, The Hand of God, and more

“It’s always rumbling. Some people find it frightening, unsettling. I love it. It energises me. The vitality feeds me.”

When’s the last time you’ve been struck?

The extraordinary does not pierce with a single thread. It cracks you through sensation, and you can’t even pinpoint where or when. Suddenly, you have goosebumps, there’s blood in your ears, tears in your eyes, sweat on your palms, a smile at the corners of your mouth. It seeps into your dreams, into your waking moments; you can’t extract it.

Art— any medium— hits at once in a million modes. I think of the final scene in Hamnet, where Agnes sees (and feels) via a play what her husband could not communicate to her in words. Through Shakespeare’s art, his inner world is conveyed.

Yes indeed; art has the power to strike, nonsensically, non-linearly, and with a magnitude of incomprehensible significance.

This is how my conversation with one of the most influential editors in contemporary European cinema begins. You may not recognise Cristiano Travaglioli’s name, but you know his award-winning work. This is the man who has shaped nine Paolo Sorrentino films— The Great Beauty, Youth, Il Divo, The Hand of God, Parthenope, to name a few. Beyond his long-time partnership with Paolo Sorrentino, Cristiano has over 35 credits to his name.

I re-watched The Great Beauty this weekend. I had forgotten what a crisp, trippy beauty it is. The party scene at the start of the film, with how many actors and extras— hundreds— and how many cameras— at least a dozen… that in itself is an editing feat worthy of reward.

I texted Cristiano the next morning. “How many hours of footage was the party scene?”

“Credo 100 ore.” (100 hours).

Can you imagine watching 100 hours of footage and choosing what stays, and how to arrange it? Just for one scene?

Cristiano has been a friend since I tried my hand at producing something of my own during the pandemic— why or how this friendship evolved, truly I do not know, but I count myself very lucky. He’s at once profound, insanely humble, and witty. Kind, compassionate, and easygoing. He always makes me laugh and always finds something to tease me about. But he also gets me. It's no surprise, considering what he does and his immense talent, that his emotional intelligence is world-class. Show him just 3% of yourself, and you will feel inexplicably understood.

I ask what he’s watched lately that affected him, which is the highest compliment one can give a work of art. You know what I mean— affectation that is physiological. If it carries any weight, a work of art hits the nervous system before it reaches the brain.

“Marty Supreme. Enjoyed that. But you know what I watched that was just… unfathomable: Twin Peaks by David Lynch. Have you heard of Stendhal Syndrome? It nearly gave me that.”

The phenomenon is usually described in museum terms: a person stands in front of a masterpiece and experiences vertigo, confusion, dizziness…you know what all these new age instagram reels tell us: your body knows before your mind.

“It's happened twice,” he tells me. “The first with Max Ernst. The second with a Raphael. And then almost with Twin Peaks, the original.” Cristiano speaks of David Lynch with acute admiration. His work is timeless and destabilising. Watching it, he needed to lean away, as if his body physically required room for what it could not metabolise.

He speaks of impact — the moment something hits with such force it’s less an object than an event. "Cinema can never do," he says, and then corrects himself with a kind of stunned reverence, because of course cinema can do it. It’s just that it rarely does anymore.

“Art has innate significance, and then you, as the viewer, add your own—however it speaks to you, whatever you hear or feel… it becomes all the more substantial. So in many ways, art is never finished. You finish it."

His perspective is quietly radical, especially in an era where films feel pressured to be comprehensive: nothing has to be complete in order to be total. It can be made of fragments. We all desire clarity, yes, but realistically, how often do we get it?

“A film can be a field of signifiers — a thousand significances,” he says, "where one detail floats along another, and meaning accumulates inside the viewer. The audience builds the bridge. "

But contemporary cinema rarely has this level of liberation. Language as form, so to speak. The audience should be able to coerce it as they desire, not be told how to chymify it.

Meaning is a rhythm. Like a dance beat. You hear your own version of it, and your body moves to that.

It’s a philosophy that makes perfect sense coming from an editor — someone whose entire job is to decide what the film doesn’t need, what it will refuse to tell you. Silence over explanation. Sequence and pulse over specific intent. This backs up why Sorrentino’s cinema lands the way it does: yes, it is lavish, baroque, electric and atmospheric, but isn’t the magic in its lack of limitation? In its irregularity?

So I am curious, especially for someone who has helped create some of modern cinema’s most iconic films: Does that sensation ever happen in his own work?

Travaglioli pauses.

"Once in a while."

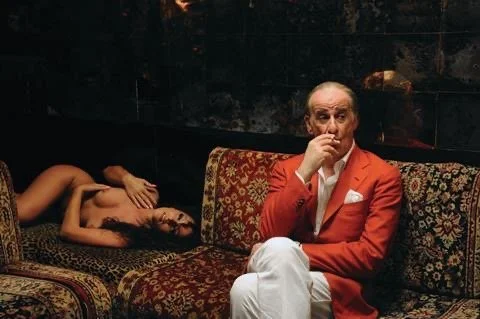

He brings up La Grande Bellezza, the film that didn’t just succeed, but became a cinematic icon, an eternal classic whose cultural footprint has only grown since it won Best International Feature Film at the Academy Awards, 35 other awards, and 41 additional nominations. This was a Rome film that became, in a way, Rome itself.

And within that film, he points to a scene where the main character, Jep, encounters a young girl. She asks a question that feels innocent, but lands existential: Who are you?

It was a quiet moment that perhaps carried the film’s entire underlying identity.

What else is he proud of, I want to know. Beyond La Grande Bellezza.

“Il Divo.”

Il Divo is audacious in the way contemporary films rarely allow themselves to be: it takes liberties and reports to no one. Sorrentino, if you know his screenplays, has an inordinate amount of irreverence, of sarcasm and spunk and ‘I don’t give a f***’ energy. The film won the Jury Prize at Cannes, a recognition of not just quality, but nerve.

“Do you listen to music while you work?”

“No, I have to listen to the film. But Paolo does. Listens to music.”

So I pivot.

I ask about his favourite places in Rome, but Cristiano needs to clarify the subject a few times, as one cannot simply ask ‘favourite restaurants’ carte blanche; one must specify. Are we talking fish? Meat? Pizza?

For fish in Rome: Bar Sotto al Mare and Pierluigi. Near the sea in Santa Marinella: Molo 21.

For Pizza in Piazza Vittorio: ArdeCore, buonissima.

Further field, in Mantova: Nizzoli, where they make tortellini mantovani alla zucca with mostarda di frutta inside. Buonissimo.

In Parma: Ai Due Platani (I’ve been here as well; it’s a must in the area. And a must-book-in-advance)

For summer travel, Travaglioli will err on the side of Boat. He is enamoured of the Aeolian Islands, Stromboli especially— a popular second home spot for Milanese and Napolitani. “Some people are very anxious about the volcano— you can always hear it, it’s always alive and rumbling. I find it… energising. The vitality feeds me.”

Then there’s Ortigia, a Sicilian city he adores and where he eats very well. At La Barca, the vibe is old school 1970s in all the best ways: fantastic atmosphere, great drinks, great music. If you’re looking for a night spot with a pulse… head here.

Back in Rome, markets matter. Mercato Trionfale for every day (I used to shop here as well and can attest). Mercato Piazza Vittorio for exotic ingredients, i.e., tropical fruit and ethnic ingredients. Outside Rome, he found a tiny market he adores: Mercato Fonte Acqua Egeria— organic, “zero kilometre,” and a fish guy so good he was, as he put it, molto colpito. Genuinely struck.

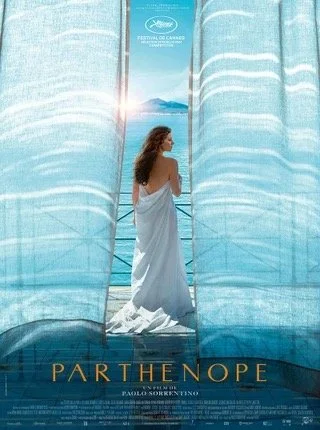

Before I let him jump onto a call concerning his current film project—about which he cannot reveal one clue— I tell him two of my favourite Sorrentino films: The Hand of God and Parthenope, which I wrote about on a substack last Spring. (I have since given up on substack— too many mediums).

Parthenope... Cristiano tilts his head... wasn’t well received. Perhaps bad timing with the culture of the moment. Critics accused it of having a male gaze.

I roll my eyes.

If Parthenope became controversial, it wasn’t because it lacked significance; it was because it was too easy to assign an argument against it. Some critics saw a beautiful woman framed by a director’s gaze and stopped there, accusing the film of existing merely to be looked at. But in Cristiano’s telling—and in mine—Parthenope isn’t a mannequin. She’s a nerve. A woman whose beauty is obvious, yes, but whose inner life is the real subject: desire as propulsion, loneliness as texture, hunger as intelligence. Cristiano tells me that a close female friend felt profoundly seen by her—a counter-reception that suggests the film didn’t fail universally, so much as split its audience along a cultural fault line.

Personally, what I connected to most was the woman herself. Her desire. Her hunger. Her loneliness. She had an aliveness that ached.

But this is where cinema is now, he says. In a culture calibrated for critique and especially during a moment of heightened sensitivity, Parthenope didn’t land the way it might have in another era. Some viewers saw only the surface. Others saw the interior life.

But ’tis the way with every piece of art, with every person we meet, with every bite of tortelli— some of those thousands of signifiers land, are interpreted one way or another, and thus the work of art becomes something else entirely.

Cristiano’s newest work, La Grazia, another Sorrentino movie, arrives in UK cinemas this March.

From La Grande Bellezza:

“Please, I’m a gentleman. Don’t destroy my only certainty.”

“Stop right there, you’re stroking my ego in a dangerous way.”